Now that Trump ( as of May 2025) has made the decision not to continue U.S. air attacks on targets in Yemen (for now), the following semi-legal analysis of the strikes below is perhaps somewhat moot. However it does provide a glimpse into the legalities of the multiple aggressions by Western countries in the past 75 years since World War 2.

After an almost shootdown of an ‘invisible’ US F35 aircraft, and the loss of 2 (possibly 3) F18s (valued at $70 million each) that had ‘fallen off’ US aircraft carriers in the Gulf, along with about 10, 30 million dollar MQ9 drones shot down by Ansar-allah (what the West MSM as one voice like to call “Iran backed rebel Houthis”-all in one breath), it must have been clearly apparent, even to Trump, that the billion dollar US bombing campaign against Yemen was going nowhere.

Additionally, because the US had (and has) very little accurate information on where Ansarallah weapons and military was on the ground they were in fact predominantly (and accidentally?) hitting civilians. In addition the long-standing U.K air support for the Americans on the Arabian peninsula was entirely without targeting or strategy, but largely an attempt to try and demonstrate that Britain was still a force to be reckoned with in the Gulf.

One cannot however be so charitable about Israeli bombings of civilian Yemen targets-(civilian ports and airports), who used their traditional methods of terror and brutality to try and intimidate Ansarallah.

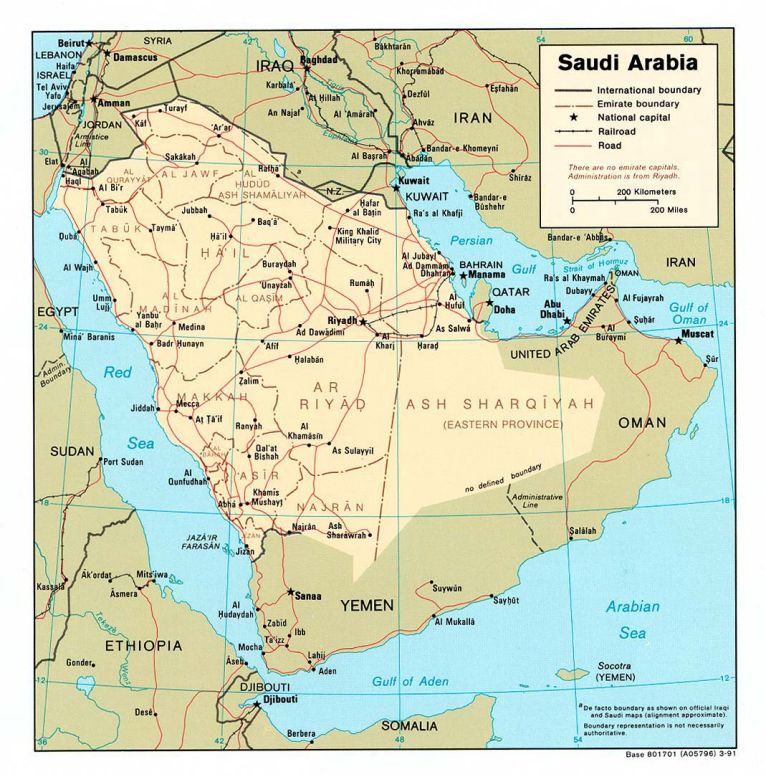

What follows is an analysis of the legalities of this bombing campaign, supposedly initiated by first Biden and then Trump, to stop Ansarallah closing the Gulf of Aden and Red Sea to shipping bound for the Israeli Red Sea port of Eilat (top right hand section of map)

Legal Analysis of US/UK Strikes in Yemen and Potential Violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL)

The US and UK military interventions in Yemen, particularly against Houthi targets, raise significant legal questions under international humanitarian law (IHL)—also known as the laws of war. Below is a deeper examination of their compliance with key legal principles.

Analysis of the Legal Framework Governing US Strikes against Yemen

A. Applicable Law

- Geneva Conventions (1949) & Additional Protocol I (1977): Govern the conduct of hostilities, including distinction, proportionality, and precautions in attack.

- UN Charter (Article 2(4) & Article 51): Prohibits the use of force except in self-defense or with UN Security Council authorization.

- Customary IHL: Binding on all parties, including non-state actors like the Houthis.

B. Justifications for US/UK Strikes

- Self-Defense Argument (Article 51, UN Charter): The US and UK argue strikes are necessary to protect maritime security (Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping).

- Legal Debate: Some scholars argue this stretches self-defense doctrine, as Houthi attacks may not constitute an “armed attack” justifying unilateral force.

- Collective Self-Defense (Supporting Saudi Arabia & UAE): Previously invoked, but less relevant post-2022 since the Saudi-Houthi truce.

2. Key IHL Principles & Potential Violations

A. Principle of Distinction (Civilian vs. Military Targets)

- Rule: Attacks must only target military objectives, not civilians or civilian infrastructure.

- Concerns in Yemen:

- Urban Warfare: Houthis embed military assets in densely populated areas, increasing civilian risk.

- Reports of Civilian Harm: NGOs (e.g., Mwatana, Amnesty) allege US/UK strikes hit homes, farms, and markets, suggesting possible indiscriminate targeting.

B. Principle of Proportionality

- Rule: Civilian harm must not be excessive relative to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.

- Challenges:

- “Double-Tap” Strikes: Some reports suggest follow-up strikes hit first responders, which could be a war crime if deliberate.

- High Civilian Toll in Past Strikes: Even if targets are legitimate, large-scale civilian casualties (e.g., 2022 Saada prison strike by Saudi coalition) raise proportionality concerns.

C. Precautions in Attack

- Rule: Parties must take all feasible measures to verify targets and minimize civilian harm.

- US/UK Practices:

- Use of precision-guided munitions (reduces but does not eliminate risk).

- Lack of Transparency: Few public investigations into alleged civilian harm, unlike in Iraq/Syria.

3. Accountability & Legal Consequences

A. Mechanisms for Accountability

- Domestic Investigations (US/UK):

- The US has a Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan (CHMR-AP) but rarely discloses Yemen investigations.

- The UK has no independent Yemen strike review body, unlike its Iraq/Syria oversight.

- International Criminal Court (ICC):

- Yemen is not an ICC member, but if nationals of member states commit crimes on Yemeni soil, the ICC could theoretically investigate.

- Universal Jurisdiction:

- Third countries could prosecute war crimes under universal jurisdiction (e.g., Germany’s case against Syrian officials).

B. State Responsibility & Reparations

- Under IHL, states must provide reparations for unlawful strikes, but neither the US nor UK has a compensation program for Yemeni victims.

- Contrast with US payments for civilian harm in Afghanistan/Iraq.

4. Broader Implications & Legal Precedents

- Escalation Risks: If strikes are seen as disproportionate, they could fuel further Houthi attacks, creating a cycle of violence.

- Erosion of IHL Norms: Repeated civilian harm without accountability weakens global adherence to laws of war.

- Potential for Future Cases: If evidence of systematic violations emerges, legal challenges could arise in international courts or via sanctions.

Conclusion: Are US/UK Strikes Lawful?

- Legally Defensible? The US/UK can argue self-defense and military necessity, but civilian harm incidents raise serious IHL concerns.

- Accountability Gap: Lack of transparent investigations and reparations undermines claims of compliance.

- Future Risks: If civilian casualties continue unchecked, legal challenges (e.g., ICC petitions, universal jurisdiction cases) could follow.